This digital publication brings together the research, production and documentation of Desire Cycle, Christopher Matthews’ trio of dance installations dealing with queer desire in three stages of life. Made between 2017 and 2024, the trilogy draws on art and dance histories, pop culture and ancient Greek philosophy to move through youth (my body’s no. 1), middle-age (Lads), and older-age (Act 3). The following archive documents the trilogy’s development and creation, alongside written reflections by academics, researchers and dance practitioners. Desire Cycle was created under Matthews’ choreographic framework formed view, an acknowledgement of the contribution made by his creative collaborators, performers and the audience to the creation and presentation of the works.

5th century BC: The Doryphoros of Polykleitos (Lads)

432 BC: Dionysus, east pediment of the Parthenon, Elgin Marble (Lads)

460-450 BC: Discobus, Myron (Lads)

428–423 BC-348 BC: Plato

385–370 BC: Plato's Symposium (Act 3)

4th century BC: Hermes and the Infant Dionysus (Lads)

circa 220 BC: Barberini Faun or the Drunken Satyr, Giuseppe Giorgetti (Lads)

100 BC–AD 200: Greco-Roman sculpture (MBNo1)

130-137 AD: The Antinous Farnese (Lads)

1500-1600: Ballet Pantomime (MBNo1)

1653: Ballet Royal de la Nuit, Louis XIV as Apollo, the Sun King (Le Roi Soleil) (Lads)

1671-1672: St. Sebastian, Guiseppe Giorgetti (Lads)

1828: Jason with the Golden Fleece, Bertel Thorvaldsen (Lads)

1879–1881: Little Dancer of Fourteen Years Old (Marie van Goethem), Edgar Degas (MBNo1)

1891-1972: Ted Shawn (MBNo1)

1911: Le Spectre de la Rose, Vaslav Nijinsky (Lads)

1912: Afternoon of a Faun, Vaslav Nijinsky (Lads)

1912–2001: Barton Mumaw (MBNo1)

1914: Postcard of Paul Swan, 'The Most Beautiful Man in the World', Rykoff Collection (Lads)

circa 1918: The Prophet Ted Shawn, Arthur F Kales (Lads)

1923: Death of Adonis, Ted Shawn (Lads)

1924: Adidas was founded

1931: Jacob's Pillow (MBNo1)

1933: Ted Shawn and his men, premiered their first performance (Act 3)

1933-1950: Queer modernism (Act 3)

1937: PaJaMa collective formed (Act 3)

1938-1993: Rudolf Nureyev (Lads)

1960: Sinner Man, Revelations, Alvin Ailey (Lads)

1960s: Go-go dancers (MBNo1)

1965: Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet Premiere (Act 3)

1976-present: Tino Sehgal

1980: Christopher's birth

1995: Swan Lake, Matthew Bourne (Lads)

July 1997: Christopher attended Jacobs Pillow, performed works of Ted Shawn (taught by Barton Mumaw) and Alvin Aileys' Sinner Man (Taught by Milton Myers and Judith Jamison)

January 1998: Sexy Boy, AIR (Lads)

2008: Christopher's first Saturn return (Adulthood)

2010-12-01: Chris was go-go dancer at Kimono Krush, Royal Vauxhall Tavern (MBNo1)

April 2013: Young and Beautiful, Lana Del Rey (Act 3)

January 2017: Shape of You, Ed Sheeran (MBNo1)

May 2017: Choreographic Coding Lab, with Naoto Hieda, sound programme for Lads was created (Lads)

June-July 2017: Residency / Presentation - The Boghossian Foundation, Villa Empain (Lads)

May 2018-05-01 00:00:00: Rehearsals (Phase 1) (Lads)

July 2018:

Residency - The Boghossian Foundation, Villa Empain (MBNo1)

Show - Art Night (Lads)

September 10th & 11th 2018: Rehearsals (Phase 2) (Lads)

September 11th 2018: Studio sharing - Chisenhale Dace Space (Lads)

September 12th 2018: Presentation - A Queer House Party, Chisenhale Dance Space (MBNo1)

September 12th & 13th 2018: Symposium - Art and Dance History, Chisenhale Dance Space (Lads)

September 28th 2018: Show - Friday Late: (De)Constructed Masculinities, V&A Museum (Lads)

January 2019:

Show - Future Oceans, The Marlene Meyerson JCC Manhattan (Lads)

Workshop - Company of Elders, Sadler's Wells (Act 3)

Residency - Dance4 (MBNo1)

September 13th 2019: Studio sharing - Dance4 (MBNo1)

July 2020: Residency - Company of Elders, Sadler's Wells (cancelled due to Covid 19) (Act 3)

June 21st-23rd 2021: Rehearsal (MBNo1)

June 24th 2021: Dress Rehearsal (MBNo1)

June 24th 2021: Private View, Sadler's Wells (MBNo1)

June 25th & 26th 2021:

Show - my body’s an exhibition, Sadler's Wells (MBNo1) (Lads)

January 2023: Research Event & Open Discussion - Festival of Learning, Independent Dance (Act 3)

November 25th 2023: First Rehearsal (Act 3)

April 10th & 11th 2024: Show - Elixir Festival, Sadler's Wells (Act 3)

April 11th 2024: Talk - In Conversation with Nicola Conibere, Sadler’s Wells (Act 3)

July 12th 2024: Presentation - Performance Lecture, Ageless Festival, Yorkshire Dance (Act 3)

2036: Christopher's second Saturn return (Maturity)

Lads (2017-18)

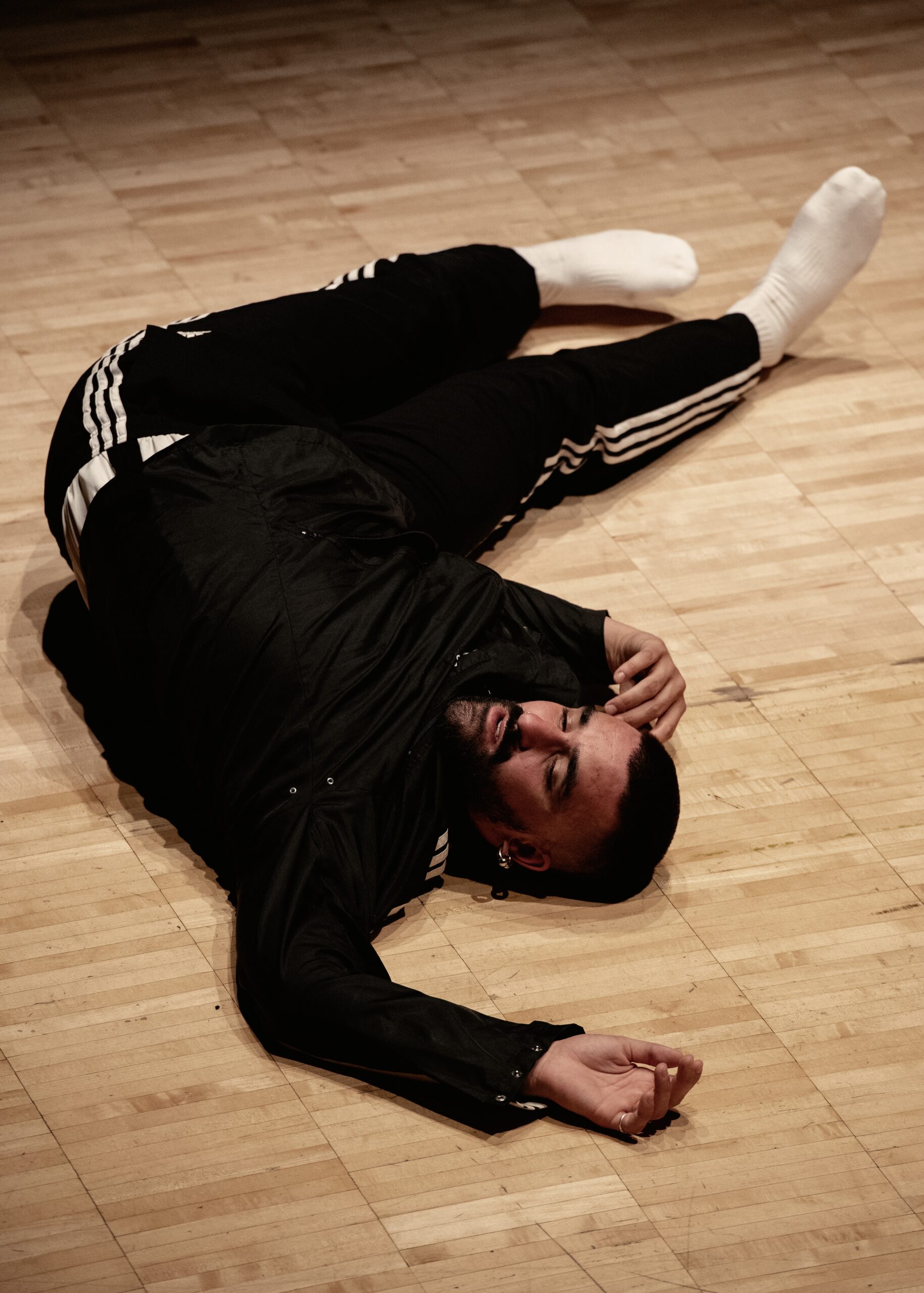

Lads is a performance piece that looks at queering masculinity in dance history, whilst questioning how class structures play a role in defining masculinity. The work reconfigures a dance battle between two figures wearing Adidas tracksuits, which sees each performer mould and move between sculptural poses from art and dance history. Through the performers’ movements and an accompanying sound piece created by Naoto Hieda using a movement responsive computer programme, the work seeks to shift traditional perceptions of time.

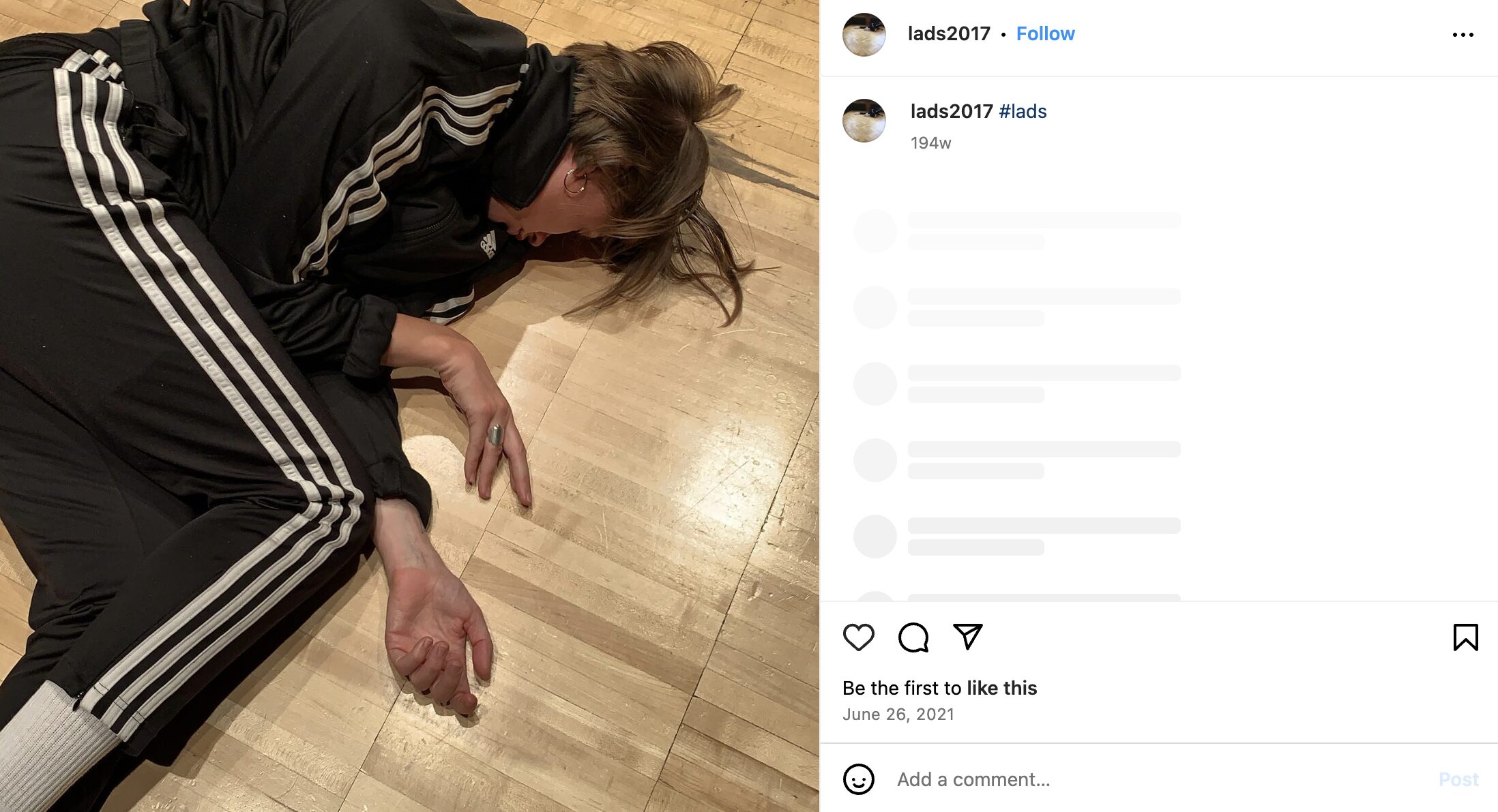

Two dancers take turns melting through eighteen poses from art and dance history. While they do so, the other photographs them on a smartphone and uploads the images to instagram.

Tags:

masculinity, dance history, art history, homoeroticism, class system

Song:

Sexy Boy, AIR

Photography:

Camilla Greenwell

Casting:

Villa Empain Residency:

Thomas Dupal, Erik Nevin

R&D:

Jessica Cooke, Andrew Graham, New Kyd, J Neve Harrington, Samir Kennedy, Samuel Ozouf, Martin Hargreaves (Dramaturgy) Shannon Stewart (Outside Eye)

Future Oceans (APAP, NYC):

Neve Harrington, John Hoobyar, Elena Light, Christopher Matthews

Sadler’s Wells (Premiere):

J Neve Harrington, Samir Kennedy, Elena Light, Christopher Matthews, Eve Stainton

Sound Design:

Naoto Hieda

Rehearsal Direction:

J Neve Harrington

Lads was supported through residencies at Villa Empain, Foundation Boghossian, Brussels and Choreographic Coding Lab Amsterdam through Naoto Hieda/Pola Arts Foundation. It was supported with funding from Sadler’s Wells Theatre and using public funding by Arts Council England.

Lads – Christopher Matthews

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 28 Sep 2018

Paul Paschal

One figure is on the ground, head down, with an arm reaching out that pulls the spine into a gentle twist. The other looms above, soft and precise as a shadow, and takes a photo on his phone. Both are dressed in immaculate Adidas black tracksuits, with the signature three bold white stripes. I shift position: from looking head-on with most of the other audience, to moving higher up on the stairs, and then returning down and kneeling close to the performers.

He sets down the phone and mirrors his twin lying on the ground. And then a third strides in. He neatly adds his shoes to the identical pairs at the side, takes a couple of photos, and then deftly folds himself into the situation as one of the others departs. Each of these entries and exits is caught by an acceleration of Naoto Hiéda’s exquisite sound design: a dream-like stop-start lurch that pulls us from an abstract soundscape of deep frequencies, to the startling clarity of Air’s hit track Sexy Boy. It helps sustain our quiet focus within the broader bustle of this late night event at the V&A.

The men continue to dance around each other. They are close enough to grapple, to fight, to clasp, to fuck – but they don’t. The image is continually kept open. Chris sits on Andrew’s elevated hips to push him back down to the ground. Sam squats over Chris as he kneels on the floor, riding him, raising and curling a clenched fist. Andrew is on the ground, and Sam stands above; his eyes and fingers flicker over his smartphone, but then he looks directly down at Andrew as he pulls his leg across to reveal his torso, face and crotch. Their feet are encased in pristine white socks. The heel of one foot is delicately and impossibly placed to rest on the toes of the other. Black silk-y plastic-y fabric stretches, pulls and folds over curves. I look at legs, hands, crotches, bellies, eyes, asses, beards, flesh and cloth.

If it’s not clear, I’m not only seduced by this work – the boldness and sophistication of the choreography – but I’m turned on by these dancing figures who luxuriate and stretch in the deliciousness of this soft streetwear. I wonder about the aesthetics and pleasures on offer here. How much is this work tied to a particularly gay male sense of texture, pleasure, and seduction? How is this choreography being read by other watchers, touchers, lovers? Lads is obsessed with these questions of codification and ownership. Despite the near-ubiquity of urban sportswear as a ‘uniform’ of contemporary dance, there’s a precision to its use here that tangibly questions how the costumes and poses of masculinity – across race, sexuality and class – are proposed, appropriated, abandoned and reclaimed.

A text on the wall describes this project as an intervention into Instagram, through its infiltration and contamination of the hetero-masculinity usually delineated by the hashtag ‘#lads’. The performers are posting the photos they are taking live on social media platforms. But I don’t have any interest in what might be happening in that digital space. Instead, I am fascinated by the presence of the performers’ cameras, and their effect in this space. It’s a performance at a busy art night, in which many people obsessively document everything they see through their camera-phone. It’s refreshing to see an artist anticipate and respond to the extraordinary image production that forms such a consistent part of the spectatorship and economy of these events.

I watch one dancer twist and pose on the ground as the other stands above him to photograph. The technological mediation of his gaze keeps their relation indirect and open; his watching echoes out to my own. I think of Leo Bersani writing about Jean Genet’s novel Funeral Rites, in which two traitorous soldiers fuck on a rooftop within war-torn Paris. One stands behind the other; rather than producing a closed unit facing each other, they both look out over the city and the night sky, opening themselves and their intimacy to the world. Lads echoes this gay male choreography of open sexuality: a public unfolding of clothing and desire and photography and possession, in which we can all open ourselves to the pleasures of becoming an image for one another.

My body's no.1 (2020)

This piece looks at queering moments in dance history through the lens of pop culture. The work sees two young ballet figures undulating in a trance-like state on two plinths or gogo boy boxes. The piece seeks to trouble the line between high art (Greco Roman nude sculptures on plinths) and low brow underground culture (gogo boys on boxes). While the audience is not addressed directly, they witness a courting between these two figures performing a seductive pas de deux. The gatekeeper of these two worlds is exposed when a figure dismounts the podium and positions themselves in the pose of the celebrated sculpture by Edgar Degas, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen.

Two dancers standing on plinths slowly gyrate in sync, with their eyes locked. Every so often one dancer performs a series of gestures taken from ballet pantomime. To signal to a dancer to come off the plinth and trade places, they recreate the posture from Degas’s Little Dancer of Fourteen Years Old and sing “your body’s number 1” in a punk style.

Tags:

Degas, go-go dancing, neo-classical nudes, ballet pantomime

Song:

Shape of You, Ed Sheeran

Photography:

Camilla Greenwell

Casting:

R&D:

fraserfab, Ryan Kirwin, Benjamin Knapper, Kanis Murillo, Dominic Rocca

Sadler’s Wells (Premiere):

fraserfab, Benjamin Knapper, Dominic Rocca, Riley Wolf

Dramaturg:

Martin Hargreaves

Producer:

J Neve Harrington

my body’s no.1 was supported through residencies at Villa Empain, Foundation Boghossian, Brussels and Dance4, Nottingham. It was supported with funding from South East Dance & Jerwood Foundation Collaborate Scheme, Sadler’s Wells Theatre and using public funding by Arts Council England.

My body's no.1 – Christopher Matthews

Dance4, Nottingham. 11 Sep 2019

Paul Paschal

Two young guys are dancing on plinths. They are variations of a type: lithe, faint stubble, defined cheekbones, white. They wear ballet school vests and tights, and a quiet confidence in their beauty. The meter-high plinths they stand on offer a certain authority – classical sculpture, visibility, leadership, sanctity – but equally render these dancers vulnerable, confined and distant.

They dance a ceaseless body-roll. An undulation passes down from head, to their neck, spine, hips and knees. Their arms reach out and down in a soft echo of go-go dancing. They are facing each other, about meter and a half apart, and staring into each other’s eyes. It doesn’t feel like an actual encounter or relationship, as much as a mirror or feedback loop, although I don’t know what it is they are looking for. Sometimes it feels like they ‘get it’, but mostly they don’t. This is a grinding dance of micro-variation, search and self-control.

I remember hearing the ballerina Sylvie Guillem describing the endlessness of her life-long training as a dancer: always striving towards, but never attaining, a greater length, height, line. I think of a gay male culture of looking, citation, body-building, pose. Elevation and emulation: I think of different figures each of us might look up to for instruction, guidance and demonstration. These two dancers are mirroring each other in close proximity; there is not enough room for us to stand before these plinths and properly submit ourselves to their authority. By doubling this dancing, Matthews prevents this audience-performer relationship resolving into anything too resolvable, or fixed.

We watch them: standing, sitting, walking a little closer or further away. Nothing much seems to change. They keep dancing this body-roll, which moves down from head to spine and knees into static feet – and from there, into these static plinths, into the static floor of this huge and quiet and otherwise-empty room. Rather than assuming the centre of this studio, they’re positioned near to one side: almost as an afterthought, indifferent to our attention. These dancers will keep going, whether an audience is there to watch them or not. I try to look away, but can’t stop seeing their shadows in my periphery, listening to their quiet breath and gasps of exertion. I think about the other people in the building who aren’t seeing this. Do they know this is happening?

This piece isn’t going anywhere: at each hour, another performer returns from his break and substitutes himself for one of the pair. I think of the costs of this dancing; the dancer’s day rate, and the significant training and bodily maintenance necessary to undertake this kind of labour. Some sculptures flex through the preciousness of their raw materials; My body's no. 1 flaunts how highly skilled and demanding this dancing is, and simultaneously how it is in a constant state of disappearance. At one point while watching, I realise that I will need to decide when I leave, to get some food, to go do some work. But how can I abandon them to this pointless labour? This isn’t tai chi, or yoga, or some other kind of nourishing or meditative movement practice – this is pure aestheticism, an evaporating image produced by two highly trained dancers relentlessly wearing their bodies down. It’s like watching gold evaporate.

So many performances within the more progressive edge of UK dance try desperately to convince the audience of the agency of their dancers. In sharp contrast, My body's no. 1 leans into the repetition, boredom and constraint that comprises so much professional dance and dance training. This work keeps on going. Dance keeps on going. Dance training keeps on going. More and more bodies submit themselves (or are submitted) to this strange and frequently violent artform that trains, constrains and displays dancing bodies.

Is the work merely reproducing the thing it is trying to critique? Some might find these classical forms repellant and boring; but others, like Matthews, keep coming back. But it’s not just charm or nostalgia or habit that ties us to these traditions. These dance forms and aesthetic values have been drilled into many of us from such a young age; inextricably and profoundly shaping us. As much as we may protest these institutions, many of us still cannot bear to step away from them – with all their elevation, beauty, constraint and precarity – and let them crumble.

Act 3 (2024)

Working with a cast of collaborators aged 60 and above – whose desire was forbidden in their youth – Act 3 considers what it means for these feelings to be hidden. Referencing Kenneth Macmillan’s Bedroom Pas de deux from Romeo and Juliet, the performance unfolds on a mattress, combining surreal visuals with an everyday setting to blur the lines between fantasy and reality. Act 3 is inspired by queer modernism and the work of photography collective PaJaMa. This collective created scenes of magical realism, featuring New York’s young bisexual or gay artists, dancers, and writers in the 1930s and 1940s.

On a mattress on the floor, one dancer slowly progresses through ten poses that recreate photos by the PaJaMa Collective. A second dancer joins them as they stand upright on the mattress, slow dance, have a whispered conversation, and hum the chorus from Young and Beautiful. A group of dancers in bathrobes watch over the ritual from the side.

Tags:

PaJaMa Collective, Paul Cadmus, Jared French, Margaret French, Ted Shawn, desire, ageism, Romeo and Juliet, Kenneth MacMillan

Song:

Young and Beautiful, Lana Del Rey

Photography:

Gigi Giannella

Casting:

Sadler’s Wells (Premiere):

Bruce Currie, Donald Hutera, Roberto Ishii, John Charles Marshall, Andy Newman, Stephen Rowe, Markus Trunk

Dramaturg:

Marnie Russell

Studio Manager:

Jenna Mason, Maya Orchin

Act 3 was commissioned by Sadler’s Wells Theatre and supported with funding from Sadler’s Wells Theatre, Independent Dance and using public funding by Arts Council England.

It was a cold day in April and a while since I had been in London, and I was intrigued to see Act Three. I had followed some of the making of the piece through one of the dancers who had shared with me a little of his own journey over the previous months of rehearsals. I felt just a little nervous on his behalf and arrived at the foyer in Sadler's Wells Theatre in plenty of time for the opening of the work. I often arrive early to enjoy the pleasure of watching people; people alone and at ease, others shifting around in a space to find their own place or greet someone they know. I had a little spot with my back to the stairs so that I wouldn’t be too distracted by the comings and goings that would inevitably happen throughout the piece.

A mattress drew my eye to the corner, the windows behind lit with bright trees in spring leaf, two benches to one side and a clock marking time. A stage of sorts. The mattress bare and white resonant with thoughts of both comfort and intimacy. I watched as some people went near and then moved away for this was a special space set apart and sacred.

And it was this sense of the sacred that for me made the work so beautiful and compelling to watch. The performers weaved around each other in a slow meditation. They communicated what seemed to me love, reverence, trust but also fear, wariness and distrust. There was power at play; the father and the son pushing and pulling away. The old bull and the new bull, an ancient story passed down through millennia; dominance and submission. There were moments of such tension that I had to look away and take a deep breath! And then another moment to look back and sense the profound love , tenderness and care that emanated from the dancing pairs.

The performers looked so exposed in their white vests and underpants. The mattress so insecure to move upon. They seemed so fragile and vulnerable to the audience as well as to their dance partners. Yet it was this intrinsic vulnerability that made the work so strong. It felt like a privilege to be witnessing something so intimate and special. As I left Sadler’s Wells the streets washed by recent rain I reflected on the scene that I had left behind. I felt that because it was set in such an open public space, with the audience drifting in and out the work was a piece of wonderful performance art. It was a kind of tableau in which we all took part as witnesses to a story, and it is this that has lingered so particularly in my mind.

I saw an albino peacock once, its plumage entirely white with no purple-blue-grey shimmer. It moved the same though, with a measured strut, mostly impressive, a tiny bit awkward.

For several hours I silently watched men watching other men on, near, or being addressed from the white mattress, framed in the glass corner. I watched fire burn through cycles of high flames and settling. White fabric repeated from ground to foot to back to front. Uniforms and sports evoked changing rooms, prisons even. I saw spaces of dressing and undressing, the collective shared individual, the pristine betraying the dirtiness. No blood, no shit, no tears. A little sweat, a fleck of spit. They made it look singular though not entirely easy, their different composures releasing, reaching, playing, forming, moving with invisible forces.

I recall the spell Act 3 cast as pairings and trios melted into each other. These are sort of interchangeable men, not as machine-like similars, as with repetition and passing on of roles gradually appears a more-than individual experience. I relish details of their different expressions, bodies, caresses. Individual men yet part of something shared beyond individual experience alone.

I recall the distance and intimacy as I watched from the side, then viewed it all from above a few flights of stairs. An almost bird’s eye view and further away but with fewer audience members in my field of vision. I felt more like a voyeur though also more relaxed to take in this intimate, timeless expression, and to film it without it being known or sensed that a lens was hovering nearby. I know that camera perceived in the peripheral vision subtly changes a sense of presentation and futurity. Maybe the peacocking wouldn’t have been disturbed, but I didn’t want to penetrate this space they held.

The event has me seeing friends appear in the audience. Seeing strangers, seeing people seeing, witnessing, attending, collectively holding vigil over something. Age? Sexuality? Surrender? The hunt and chase? I thought about abandon and being abandoned, about types of freedom, constraint, loss. I felt through about misleading perceptions of other people. I thought about making visible less visible actions or desires that might in another context be terrifying, too personal, too precious to expose or risk.

Within the cycles there was always a section of inaudible speech, discernible in its intensity but semantically unclear. A seduction, a persuasion, a confession? Animation of the face and eyes in a mumbled time. Not knowing something that wasn’t mine to know.

Addendum

Christopher Matthews’ practice spans choreography, installation and visual art. As a former repertory dancer trained in classical ballet, early modern dance and classical and commercial jazz, his work is deeply embedded in performance. Matthews uses these performed and constructed dance histories at the core of his work, considering his craft not only a tool to serve an idea, but as something to be investigated. Thematically, Matthews’ works are on the subjects of spectatorship, gender, body image, queerness, class, and the intersections of the classical and the contemporary. Often making works for gallery and museum rather than theatre contexts, Matthews’ projects take the form of live sculptures – durational works that unfold over the course of several hours. Much of his work is created under his choreographic framework formed view. This agreement or open collective is an acknowledgement of the contribution made by his creative collaborators, performers and the audience to the creation and presentation of the works.

Christopher Matthews is an award winning American-born choreographer, performer and visual artist working from London. Matthews holds a BFA from New York University Tisch School of the Arts and an MA in Choreography from Trinity Laban. His video and performance works have been presented internationally, including at the Victoria & Albert Museum, Sadler’s Wells, Art Night 2018, Yorkshire Dance, Enclave Gallery, Arbyte Gallery, ]performance space[, Chisenhale Dance Space, MonArt Digital Art, CollectArt, LimaZulu, 4BID Gallery, Mount Florida Gallery, Castlefield Gallery, Prism Contemporary, Millennium, Reykjavik Dance Festival, Cent Quatre, MCLA Gallery 51, Villa Empain, Loop Video Art Festival, and was named a 2024 Blue Chip Finalist. As a performer, Matthews works with Trajal Harrell on his national and international presentations. He is a dancer in the Oscar-winning blockbuster Wicked directed by John Chu, and the film The Magic Faraway Tree.

Burt, Ramsay. The Male Dancer : Bodies, Spectacle and Sexualities. London, Routledge, 1996.

Croft, Clare. Queer Dance. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Dolin, Anton. Pas de Deux. Courier Corporation, 1 Jan. 2005.

Hocquenhem, Guy. Homosexual Desire. London Allison & Busby, 1978.

Homans, Jennifer. Apollo’s Angels. Granta Books, 3 Jan. 2013.

hooks, bell. The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love. New York, Washington Square Press, 2004.

Kemp, Jonathan. The Penetrated Male. Brooklyn, Ny, Punctum Books, 2013.

Kopelson, Kevin. The Queer Afterlife of Vaslav Nijinsky. Stanford, Calif., Stanford University Press, 1997.

Laurens, Camille. Little Dancer Aged Fourteen. Other Press, LLC, 20 Nov. 2018.

Lee, John Alan. Gay Midlife and Maturity. Routledge, 1991.

Londraville, Janis, and Richard Londraville. The Most Beautiful Man in the World : Paul Swan, from Wilde to Warhol. Lincoln, University Of Nebraska Press, 2006.

Lord, Catherine, and Richard Meyer. Art & Queer Culture. London, Phaidon Press, 2013.

Michel, Alice. Degas and His Model. David Zwirner Books, 22 Aug. 2017.

Mitchell, Larry, et al. The Faggots & Their Friends between Revolutions. New York, Nightboat Books, 2019.

Nikolaĭ Nikolaevich Serebrennikov, and Joan Lawson. The Art of Pas de Deux. Princeton, Nj, Princeton Book Co, 1989.

Parlett, Jack. Fire Island. Granta Books, 26 May 2022.

Parry, Jann. Different Drummer : The Life of Kenneth MacMillan. London, Faber, 2010.

Plato. Plato. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press ; London, 1975.

Reed, Christopher. Art and Homosexuality : A History of Ideas. New York, Oxford University Press, 2011.

Rickard, George. Practical Mining. 1869.

Scolieri, Paul A. Ted Shawn : His Life, Writings, and Dances. New York, Oxford University Press, 2019.

Shakespeare, William. The New Clarendon Shakespeare. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1966.

Sherman, Jane, and Barton Mumaw. Barton Mumaw, Dancer : From Denishawn to Jacob’s Pillow and Beyond. Hanover N.H., Wesleyan University Press, 2000.

Stoneley, Peter. A Queer History of the Ballet. London ; New York, Routledge, 2007.

Thomas, Helen. Dance, Gender and Culture. Springer, 15 June 1993.

The research and making of The Desire Cycle has inspired a number of additional digital, 2D and performance works. These projects – some of which have been fully realised and presented, and some which remain nascent ideas – exist as thematic offshoots or extensions to the trilogy.

Lads

#Lads:

The #Lads hashtag is usually reserved for traditional displays of masculinity and normative gender roles. Alongside the performance installation, this virtual space is occupied and co-opted with contrasting critical images to explore how the work collides with popular culture. Audiences are invited to post photos and videos of the work, or others of their choosing, onto Instagram using the hashtag #Lads.

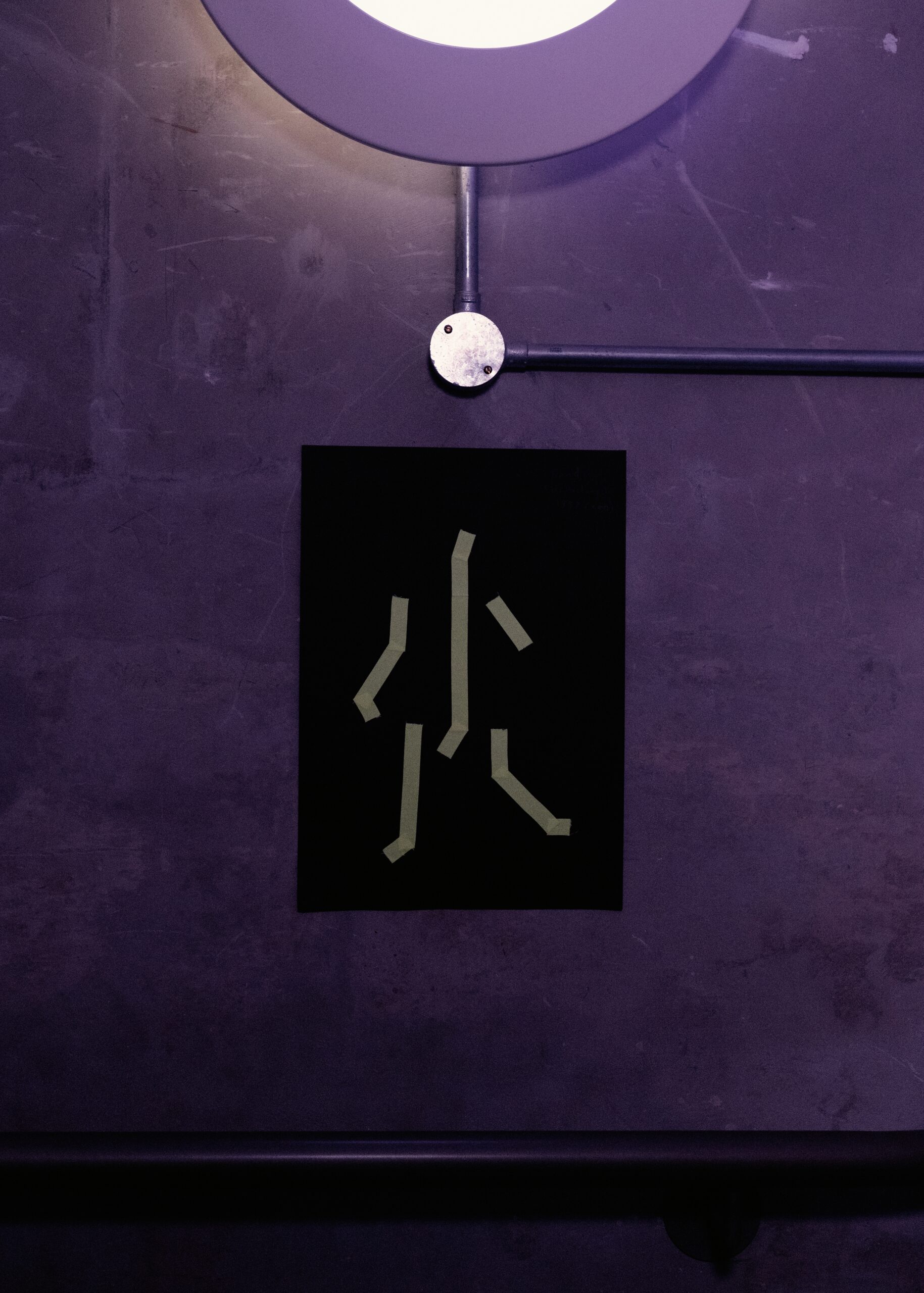

Raining Men:

In this installation, elevated printers rain printouts of photos that have been posted on Instagram with the hashtag #lads, confronting the visitor with a live, physical display of a social media feed. Digital clutter re-enters the real world in real time, embodying the weight and waste inherent in digital documentation and dissemination, as well as questioning ideas of ownership and privacy relating to social media. At the end of each day the printed photos are collected and turned into notebooks or collaged decoupage furniture.

my body’s no.1

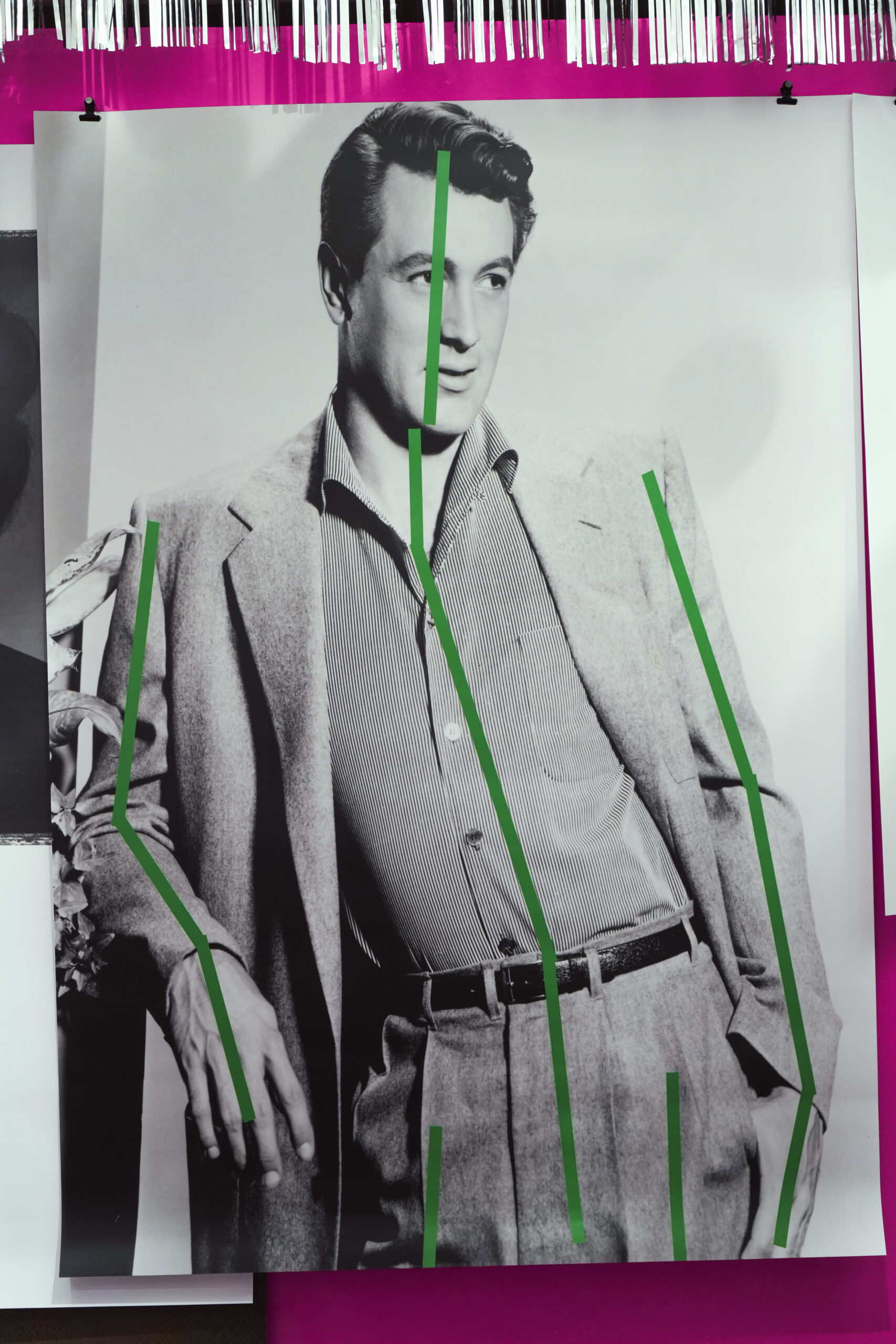

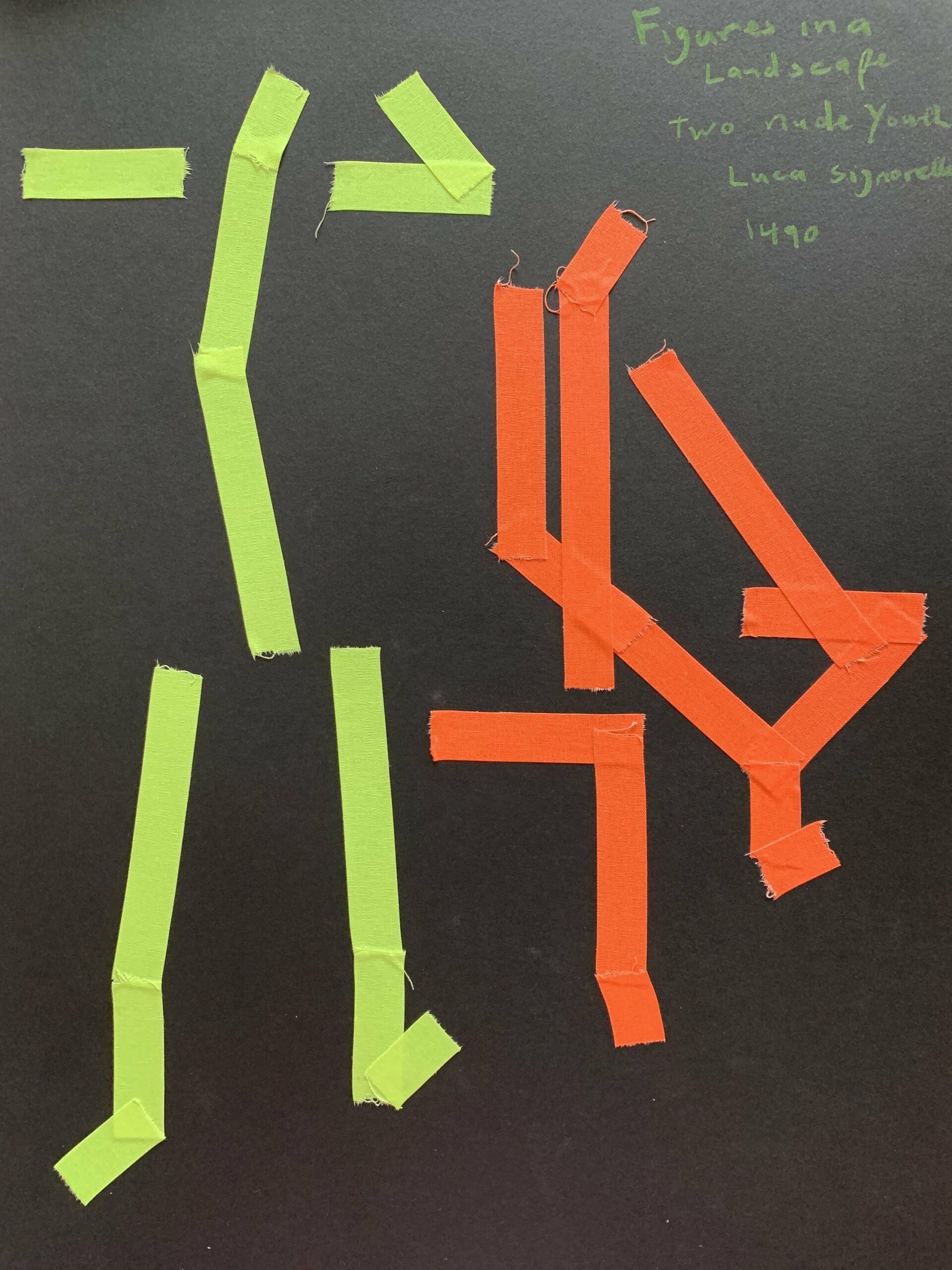

Broken Lines:

During his student years in New York, Matthews asked his friend Erickatoure Aviance how you can tell if someone is gay (it was still relatively dangerous to approach strangers in those days). Without a beat she replied ‘just look for the broken lines, gurl’. Her insinuation that gay men carry their bodies differently to the stiff, stick figure heterosexual American man – how they sit into their hips, a dropped wrist, the line of their fingers – has stayed with Matthews ever since. Broken Lines plays with campness and the way the body performs the codes of gesture. In these 2D works, Matthews reduces historical figures and art works down to their lines, looking at their postures and posings. Focusing on works that present the male figure in positions of power or desire, he highlights the “camp line” in these shows of masculinity and hierarchy.

Act 3

Hey boo:

Hey Boo is a performance installation that sees performers greeting visitors with a cheeky “hello” as they enter a gallery, whilst dancing to music in their headphones. Inspired by the afternoon tea concerts held by dance pioneer Ted Shawn at his farm Jacob’s Pillow, in which his dancers wore bathrobes and served tea to patrons before performances, the work questions the role of the performer and service they provide.

Photo: Josh Hill

for the boys

dance history boys, art history boys, pop culture boys

the boys studying dance

the boys making art

the boys made of stone

the boys in tights

the queer boys

especially those boy who are the shoulders I stand on

Muna, for you constant encouragement and support. Robyn Cabaret for standing by me and the works. Christopher Haddow for the endless support. Zeynep Gunaydin for your support and bringing Act 3. Sadler’s Wells Theatre and Alistair Macauley. Company of Elders and Elaine Foley. Asad Raza for the invitations to the Villa Empain. Jenna Mason, our first meeting at the V&A you were wearing overalls and I knew we were going to be friends. Thank you for the continued support. Neve Harrington for your tireless support with the early stages of the trilogy. The project would haven’t gotten off the ground without your rigorous commitment. EJ Gonzalez, Eve Stainton, Rory Pilgrim and Shannon Stewart for your support during the R&D of Lads. Maya Orchin for being there and lifting me up. And Andrew Sanger for your wisdom and support. John Philip Sage and Carlos Romo-Melgar for your ingenious creativity. Arabella, for the best inspiring conversations in the world!

For every single person who came to see and support the works.

And Janet,

I am forever grateful for your inspiration.